Einsiedeln, the monastery village

People mostly visit Einsiedeln because of the monastery. Arriving for the first time, they might feel a bit irritated.

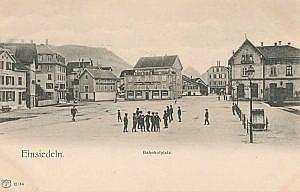

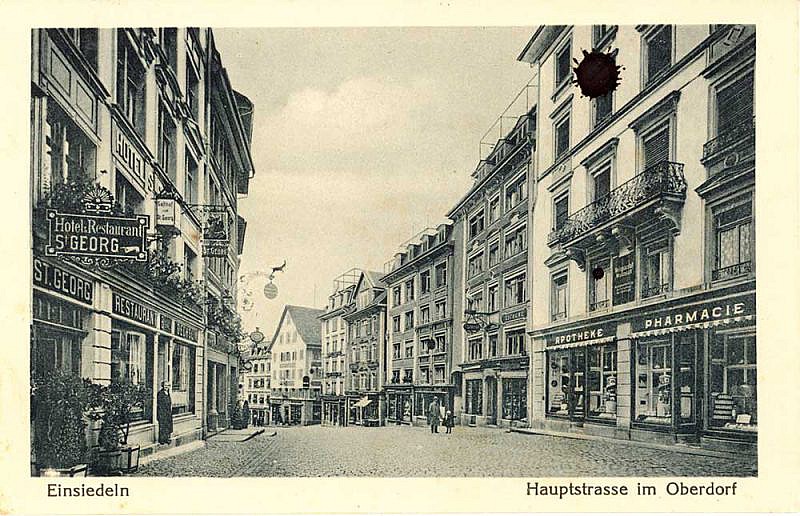

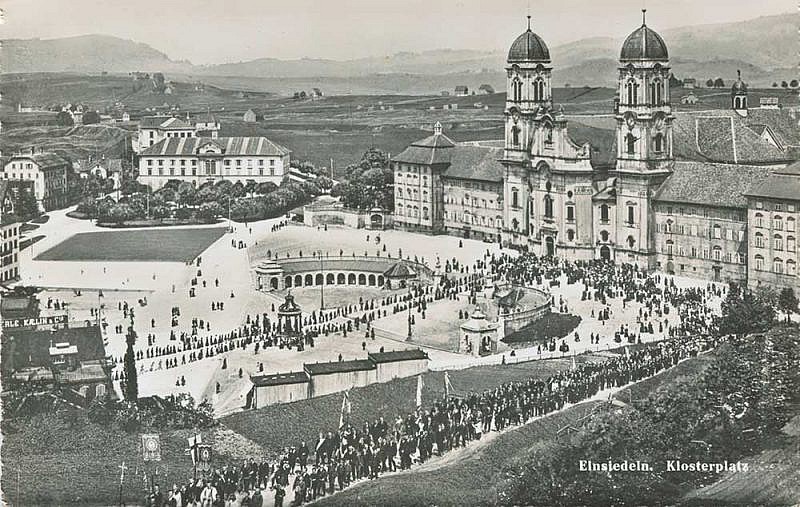

No historical old part of town that gives a taste of the Middle Ages may be found there. The way from the train station leads visitors through a busy village core and passes modern commercial establishments and restaurants, functional bank buildings, and hotels built in the late 19th century. Only at the road’s end, visitors get a sudden view of the baroque monastery facade. In solitary splendor it stands majestically and imposing over the village.

The monastery boasts of a more than one thousand year history. A first settler in the region was Saint Meinrad, a monk of the monastery Reichenau, who retired as a hermit to the “Finstere Wald”, the dark forest, but in 861 he was killed by two robbers. In 934 a clergyman of Strasbourg in present-day France founded a Benedictine monastery where Meinrad’s cell once stood. The monastic community endured. It marks the history of the whole region and has played a central role in the area not in the least as a big farmstead, a commercial center, and an important employer. Earlier, for instance, the monastery’s horse breeding was known far beyond the country’s borders. Until political and social changes swept Europe after 1800, the monastery dominated the region politically as well as economically. Thus the history of the village evolved in the shadow of a most powerful monastery. Only during the 19th century were Einsiedeln’s villagers able to overcome its dominance. But also since then, and until today, the village could not and cannot function without the monastery. The task has always remained to find ways to accommodate each other and to reach agreement. A main reason for this is tied to pilgrimage that is as important to the monastery as it is to the village.

Einsiedeln, place of pilgrimage

Since the 14th century already Einsiedeln was an internationally important Catholic place of pilgrimage. The goal of pilgrims is the Black Madonna, a late Gothic statue of Mary that is believed to work miracles. The number of pilgrims varied off and on, but on the whole has remained astonishingly constant throughout the ages. In peak years of the nineteenth century up to 200,000 pilgrims annually visited Einsiedeln. The village people gained economically from those pilgrims. Hosts and hostesses as well as people selling prayer books or producing devotional items and souvenirs made good money that at times led to the reproach that they were engaged in a hidden “mercantile Catholicism”. Of course, throughout the centuries, pilgrimages were for the faithful also partially a “pleasure trip” that provided not only spiritual but also physical enjoyment. Today spiritual and secular motives are even more powerfully mixed. About two million people visit Einsiedeln every year, mostly as day tourists, and besides traditional groups of religious pilgrims there are also people engaged in winter sports, hiking, and the pursuit of cultural interests. Today Einsiedeln is becoming a recreational region for metropolitan Zurich, but like before, there are also visitors to the monastery village from all over the globe.

Einsiedeln and the World

There was always a busy coming and going in Einsiedeln. Among the hosts of pilgrims there were also beggars and all kinds of peddlers. Some famous people too found their way to the monastery village, as for instance Johann Wolfgang von Goethe who arrived in 1775 and wrote “of the rugged paths that led to Einsiedeln.” Also the fairytale author Hans Christian Andersen or the greatest lady killer of world literature Giacomo Casanova went to Einsiedeln, the latter apparently seriously considering becoming a monk of the monastery. In turn, the villagers of Einsiedeln went to all corners of the world and had commercial ties abroad. Peddlers from Einsiedeln visited nearby foreign regions and sold rosaries, prayer books, and all kinds of devotional items. Also among the hundred thousands of mercenary soldiers who served foreign powers until the mid-nineteenth century were many men from Canton Schwyz and Einsiedeln. As to exports, the most important products were milk cows of central Switzerland. In fall, Einsiedeln farmers and cattle raisers drove their animals for days over the Gotthard Pass to sell them to traders in Italian towns. This form of migratory mobility was joined by emigration overseas and was often permanent. By 1950 several thousand people from Einsiedeln had left for America.

Who in the region did not have a brother, sister, cousin, or at least an acquaintance living “over there” who occasionally might send a letter?

Some went, some arrived. The dam and the bridges over the Sihl Lake near Einsiedeln that were built in the 1930s could hardly have been accomplished without guest workers from southern Switzerland or Italy. For a long time Einsiedeln also attracted advocates of international political Catholicism. It offered an opportunity to show abhorrence for the “unchristian spirit of modernity”. In the second half of the twentieth century Einsiedeln, in step with the Catholic Church in Europe, lost significance. Large religious events, however, continue to be held as before. In these days, Einsiedeln is hosting several large pilgrimage events of various ethnic groups and nationalities. Large groups of Portuguese, Tamil, Croatians, and others come to Einsiedeln, but they conduct their festivities their own way in which religious service is but one element.

Einsiedeln: A place of education and culture

In many parts of the world, monasteries are centers of culture. Also in Einsiedeln. If one speaks of art, culture, and learning in the context of Einsiedeln, one means the monastery, its baroque architecture, its library representing an ancient book culture; one thinks also of organ concerts and other cultural events in the monastery, perhaps also of the extensive historical collections of cultural and natural artifacts that monks have created over the centuries. Many will also think of the monastery school that since federal recognition in 1872 has been attended by thousands of young men and women, who studied there and graduated from college. For many, Einsiedeln is a place of a so-called “altehrwürdige”, that is, most venerable culture. Always the monastery is meant, never the village.

The curved plaza before the monastery is not only a unifying symbol in which the secular and spiritual come together, but it also signifies the separateness of the monastery and the village. The village has its own identity which ¬– admittedly in difference from the monastery – it has created on its own.

Rural Einsiedeln

There is a long tradition in Einsiedeln that features the village in the tradition of the hermitage of Saint Meinrad as a forlorn place far from world events. Old names for Einsiedeln such as “Finsterer Wald”, dark forest, or “Heilige Wüste”, holy desert, hint at it. The self-image of an isolated spot in the Swiss Alps in exaggerated form also shapes the numerous postcards of the so-called “Belle Époque”, the years between 1871 and the onset of World War One.

The district Einsiedeln includes not only the small town, that today counts about 9,500 people, and the monastery, but it also encompasses the six surrounding villages of Bennau, Egg, Euthal, Gross, Trachslau, and Willerzell that are called “Quarters” and are engaged in cattle raising. For these surroundings Einsiedeln functions as a center. For larger purchases inhabitants of the Quarters visit the village, the seat also of administration and having a hospital and a high school; people are also attracted to the village by cultural events and night entertainment. The region and its inhabitants have preserved their rural character. Many Einsiedeln people are proud of their traditions that didn’t adopt urban traits, of their unique dialect, and of their intense community life centered in social associations. These count over one hundred and include numerous sport clubs, more than thirty music and song associations, and also theater and cultural groups. Local rural customs are more significant than the initiatives of the “high culture”. For instance the “Fastnachtszeit”, the weeks before Lent, put Einsiedeln into a special pattern. Within weeks several traditional masked dances and parades are held; groups of men, the so-called “Trichler”, march through the village, children as well as adults put on fancy dress and costumes, and many create their own masks and build uniquely adorned wagons. The high point is the so-called “Monday of Roses”, in Einsiedeln-German dialect called “Güdelmäntig”, Belly Monday. Just two days before Ash Wednesday when the forty-day season of Lent begins, there is one more boisterous and loud festivity. But there are also other customs and traditions being preserved such as the yearly exhibition of cattle. Those Einsiedeln people, they know how to celebrate their feasts; but they consider themselves also skilled in management and strive for social cohesion.

Many appreciate the village’s social network with all its conventions, but others view village life as narrow, even as stifling.

Booming Einsiedeln

In 1850 Einsiedeln belonged to the largest 15 places of Switzerland. Later population growth stagnated so that the town had fewer inhabitants in 1950 than in 1880. During the last twenty-five years the population has been growing again. In 1990 some 10,000 people were living in the district, today there are more than 15,000. Today the region faces a transformation, however; it has moved into the radius of forty miles distant metropolitan Zurich with all the infra-structural demands this entails. At the periphery of the village and in the Quarters new residential areas have emerged, in the core of the village new business establishments and apartment buildings been established. Many new arrivals are young families that appreciate the rural environment where they can better afford rents or buy land than in the cities. There are also astonishingly many Einsiedeln people who for years lived, studied, or worked elsewhere, but then return to their place of origin some time in their adult years.